Whole grains have phytochemicals with health-promoting activity equal to or greater than that of vegetables and fruits. This was reported at the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) International Conference on Food, Nutrition and Cancer, by Rui Hai Liu, M.D., Ph.D., and his colleagues at Cornell University. Research showed that whole grains, such as whole wheat, contain many powerful phytonutrients whose activity has gone unrecognized because research methods have overlooked them.

Despite the fact that for years researchers have been measuring the antioxidant power of a wide array of phytonutrients, they have typically measured only the "free" forms of these substances, which dissolve quickly and are immediately absorbed into the bloodstream. They have not looked at the "bound" forms, which are attached to the walls of plant cells and must be released by intestinal bacteria during digestion before they can be absorbed.

Phenolics, powerful antioxidants that work in multiple ways to prevent disease, are one major class of phytonutrients that have been widely studied. Included in this broad category are such compounds as quercetin, curcumin, ellagic acid, catechins, and many others that appear frequently in the health news.

When Dr. Liu and his colleagues measured the relative amounts of phenolics, and whether they were present in bound or free form, in common fruits and vegetables like apples, red grapes, broccoli and spinach, they found that phenolics in the "free" form averaged 76% of the total number of phenolics in these foods. In whole grains, however, "free" phenolics accounted for less than 1% of the total, while the remaining 99% were in "bound" form.

In his presentation, Dr. Liu explained that because researchers have examined whole grains with the same process used to measure antioxidants in vegetables and fruits—looking for their content of "free" phenolics"--the amount and activity of antioxidants in whole grains has been vastly underestimated.

Despite the differences in fruits', vegetables' and whole grains' content of "free" and "bound" phenolics, the total antioxidant activity in all three types of whole foods is similar, according to Dr. Liu's research. His team measured the antioxidant activity of various foods, assigning each a rating based on a formula (micromoles of vitamin C equivalent per gram). Broccoli and spinach measured 80 and 81, respectively; apple and banana measured 98 and 65; and of the whole grains tested, corn measured 181, whole wheat 77, oats 75, and brown rice 56.

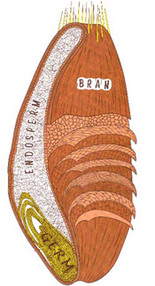

Dr. Liu's findings may help explain why studies have shown that populations eating diets high in fiber-rich whole grains consistently have lower risk for colon cancer, yet short-term clinical trials that have focused on fiber alone in lowering colon cancer risk, often to the point of giving subjects isolated fiber supplements, yield inconsistent results. The explanation is most likely that these studies have not taken into account the interactive effects of all the nutrients in whole grains—not just their fiber, but also their many phytonutrients. As far as whole grains are concerned, Dr. Liu believes that the key to their powerful cancer-fighting potential is precisely their wholeness. A grain of whole wheat consists of three parts—its endosperm (starch), bran and germ. When wheat—or any whole grain—is refined, its bran and germ are removed. Although these two parts make up only 15-17% of the grain's weight, they contain 83% of its phenolics. Dr. Liu says his recent findings on the antioxidant content of whole grains reinforce the message that a variety of foods should be eaten to achieve good health. "Different plant foods have different phytochemicals," he said. "These substances go to different organs, tissues and cells, where they perform different functions. What your body needs to ward off disease is this synergistic effect—this teamwork—that is produced by eating a wide variety of plant foods, including whole grains."

Source

Rui Hai Liu on Studying the Health Benefits of Whole Foods Scientist Interview: January 2012

Despite the fact that for years researchers have been measuring the antioxidant power of a wide array of phytonutrients, they have typically measured only the "free" forms of these substances, which dissolve quickly and are immediately absorbed into the bloodstream. They have not looked at the "bound" forms, which are attached to the walls of plant cells and must be released by intestinal bacteria during digestion before they can be absorbed.

Phenolics, powerful antioxidants that work in multiple ways to prevent disease, are one major class of phytonutrients that have been widely studied. Included in this broad category are such compounds as quercetin, curcumin, ellagic acid, catechins, and many others that appear frequently in the health news.

When Dr. Liu and his colleagues measured the relative amounts of phenolics, and whether they were present in bound or free form, in common fruits and vegetables like apples, red grapes, broccoli and spinach, they found that phenolics in the "free" form averaged 76% of the total number of phenolics in these foods. In whole grains, however, "free" phenolics accounted for less than 1% of the total, while the remaining 99% were in "bound" form.

In his presentation, Dr. Liu explained that because researchers have examined whole grains with the same process used to measure antioxidants in vegetables and fruits—looking for their content of "free" phenolics"--the amount and activity of antioxidants in whole grains has been vastly underestimated.

Despite the differences in fruits', vegetables' and whole grains' content of "free" and "bound" phenolics, the total antioxidant activity in all three types of whole foods is similar, according to Dr. Liu's research. His team measured the antioxidant activity of various foods, assigning each a rating based on a formula (micromoles of vitamin C equivalent per gram). Broccoli and spinach measured 80 and 81, respectively; apple and banana measured 98 and 65; and of the whole grains tested, corn measured 181, whole wheat 77, oats 75, and brown rice 56.

Dr. Liu's findings may help explain why studies have shown that populations eating diets high in fiber-rich whole grains consistently have lower risk for colon cancer, yet short-term clinical trials that have focused on fiber alone in lowering colon cancer risk, often to the point of giving subjects isolated fiber supplements, yield inconsistent results. The explanation is most likely that these studies have not taken into account the interactive effects of all the nutrients in whole grains—not just their fiber, but also their many phytonutrients. As far as whole grains are concerned, Dr. Liu believes that the key to their powerful cancer-fighting potential is precisely their wholeness. A grain of whole wheat consists of three parts—its endosperm (starch), bran and germ. When wheat—or any whole grain—is refined, its bran and germ are removed. Although these two parts make up only 15-17% of the grain's weight, they contain 83% of its phenolics. Dr. Liu says his recent findings on the antioxidant content of whole grains reinforce the message that a variety of foods should be eaten to achieve good health. "Different plant foods have different phytochemicals," he said. "These substances go to different organs, tissues and cells, where they perform different functions. What your body needs to ward off disease is this synergistic effect—this teamwork—that is produced by eating a wide variety of plant foods, including whole grains."

Source

Rui Hai Liu on Studying the Health Benefits of Whole Foods Scientist Interview: January 2012

RSS Feed

RSS Feed